Why doesn't the USA legalise cannabis at the federal level?

List of contents

In 2012, Colorado and Washington made headlines when they became the first two US states to legalise cannabis for recreational use. Since then, 18 more states, as well as the District of Columbia, have followed suit by passing laws for distribution and recreational consumption.

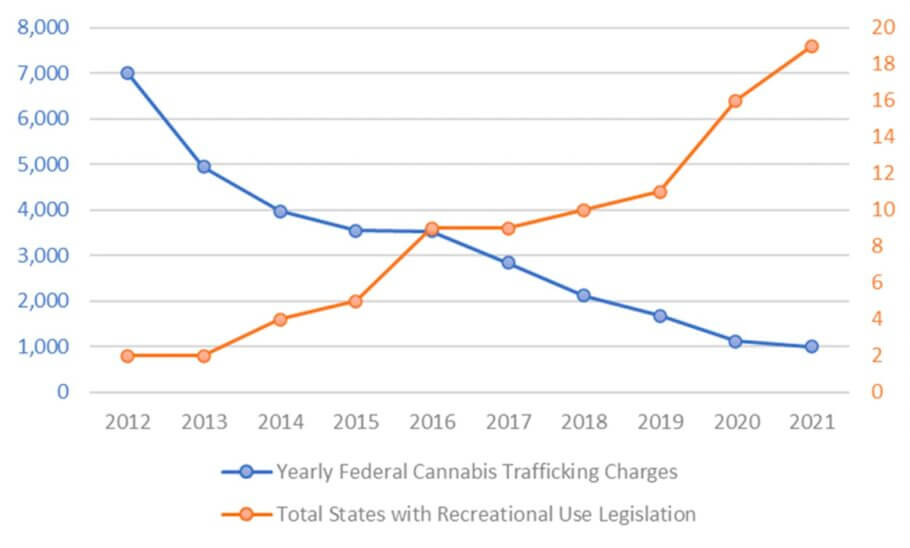

Classified as a Schedule I drug by the Controlled Substances Act, just like methamphetamine or cocaine, cannabis remains illegal at the federal level. However, as more state legislators pass legislation to legalise recreational use, federal cannabis trafficking cases and charges have steadily declined year over year.

According to the US Sentencing Commission's 2021 Sourcebook, in 2012, the same year that Colorado and Washington first passed their legislation, federal prosecutors charged approximately 7,000 people with marijuana trafficking. Cannabis accounted for 27.6% of all drug trafficking charges that year, the most of any substance category.

As other states continued to pass laws to legalise recreational cannabis, the number of federal trafficking charges began to decline year on year. In 2016, when a total of nine states had opened up to recreational use, cannabis trafficking cases fell by about half to 3,500 cases.

More recently, in 2021, that number fell below 1,000 for the first time in this period, with a total of 996 people charged with cannabis trafficking, representing just 5.7% of total federal drug trafficking cases, the lowest rate of all the main categories.

However, despite the evidence offered by the decrease in data on arrests for marijuana trafficking, the federal prohibition of cannabis at the national level remains unchanged, anchored in a past from which, for more than half a century, it has been incapable of leaving behind.

A brief history of the decriminalisation of cannabis in the US

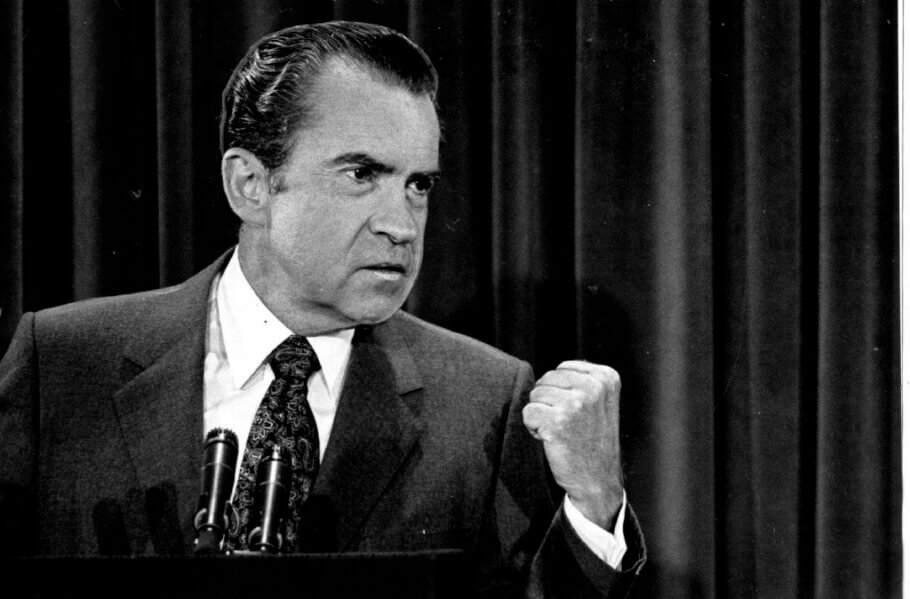

Just fifty years ago, the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse issued a report that was probably quite different from what President Richard Nixon had expected when he appointed a committee of experts (chaired by former Pennsylvania Governor Raymond Shafer) to deal with the issue of cannabis decriminalisation. From the perspective of a president who the previous year had declared drugs "America's Public Enemy Number One", the report's title "Marihuana: a symbol of misunderstanding" was hardly promising.

"Criminal law is too harsh a tool to apply to personal possession [of marihuana] even in an effort to discourage use," the Shafer Commission concluded. "It involves an overwhelming indictment of behavior we believe is inappropriate. The actual and potential harm of drug use is not great enough to justify the criminal law's intrusion into private behavior, a step our society takes only with the greatest reluctance".

Based on that assessment, the report recommended that "possession of marihuana for personal use should no longer be a crime" and that "casual distribution of small amounts of marihuana for no or negligible remuneration should no longer be a crime". That policy, which became known as the "decriminalisation" of marijuana, went nowhere under the Nixon administration.

But during that decade, beginning with Oregon in 1973, nearly a dozen states followed the commission's advice and generally changed low-level possession from a criminal offence to a civil violation punishable by a modest fine. President Jimmy Carter supported decriminalisation in 1977 when he told Congress that "sanctions against possession of a drug should be no more harmful to an individual than the use of the drug itself".

Meanwhile, to this day, Congress has yet to follow the Shafer Commission's recommendation made half a century ago. At the federal level, cannabis remains illegal for all intents and purposes, and even low-level possession remains a crime. Even relatively modest attempts to address the conflict between state and federal cannabis laws failed to make progress in the Senate.

Current President Joe Biden, a long-time drug opponent who now presents himself as a reformer, says he supports federal decriminalisation of cannabis use and that he believes states should be free to legalise. But unlike almost every other candidate he defeated for the Democratic presidential nomination, he opposes repealing federal cannabis prohibition.

Biden pledged that he would "extensively use his power of clemency" to commute the sentences of non-violent offenders and specifically said that anyone convicted of cannabis-related offences "should be released from prison". But so far he has not used his power of clemency at all.

Biden also talked about facilitating medical research by reclassifying cannabis under the Controlled Substances Act, which can be done administratively, without any new legislation. But, as simple as it would be, he has not taken any steps in that direction either.

Since 1969, the Gallup poll has asked Americans whether "marijuana use should be legal". The proportion of people who answered yes rose from 12% in 1969 to 28% in 1977, then fell to 23% in 1985 before beginning a gradual climb in the mid-1990s. According to the latest Gallup poll, two-thirds of Americans think cannabis use should be legal. However, President Biden is apparently unimpressed by this sea change in public opinion.

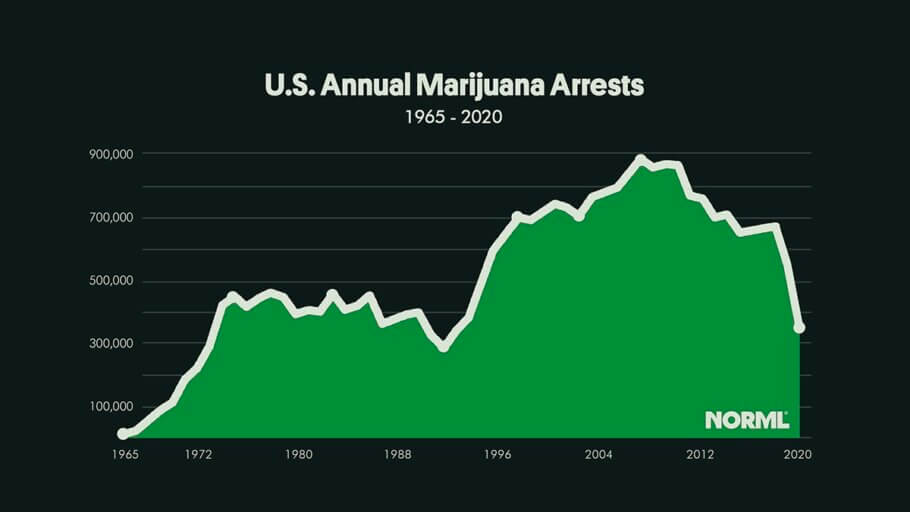

Arrests as a disproportionate response to cannabis use

The same year that the Shafer Commission report was published, US police made about 292,000 arrests for cannabis use and possession, up from 226,000 the year before. That number had risen to approximately 446,000 by 1978. It ebbed and increased over the next decade before beginning a steep ascent in the early 1990s, peaking at about 873,000 in 2007. In 2020, the total was about 350,000, 36% less than the previous year and 60% lower than the 2007 peak.

The vast majority of these cases (91% in 2020) involved low-level possession, which corresponds to the arrests that the Shafer Commission said should have ended half a century ago. In absolute terms, the 2020 total was even higher than the 1972 number. But adjusting for population growth, the marijuana arrest rate fell by about 24%, from 139 to 106 per 100,000 Americans.

Cannabis advocates argue that the year-on-year decline in both trafficking and possession arrests corresponds with the growing number of states that have implemented legalisation and provided consumers with legal outlets to purchase cannabis; it also reflects a loss of federal priority in prosecuting cases despite ongoing prohibition. Meanwhile, the war on weed continues to lose voter support.

While there may be no single factor contributing to this trend, it seems likely to continue, both because more states are working to end prohibition and because the Federal Justice Department is led by an Attorney General who has repeatedly asserted that cannabis prosecution at the user level is a waste of government resources.

The American Civil Liberties Union estimates that the US spends more than $3.6 billion a year enforcing cannabis prohibition, compared to about $3.7 billion in tax revenue that states earned from recreational cannabis sales in 2021. And the majority of the more than 350,000 annual arrests that occur largely involve people of colour, who are nearly four times more likely to be arrested than white people - an even greater social injustice.

The never-ending (political) story

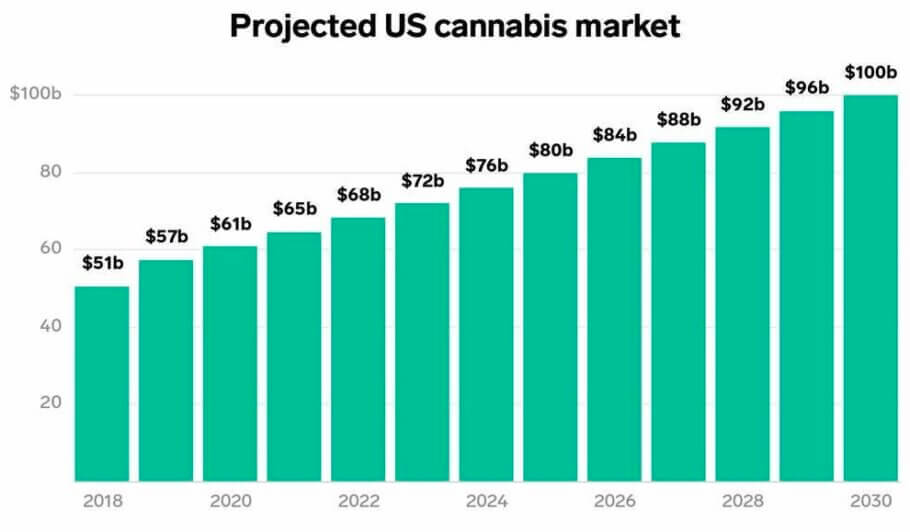

However, as arrest numbers decline each year, as more states move to decriminalise and legalise cannabis, and as the economic benefits of the legal marijuana industry become more apparent (last year, annual cannabis sales reached $26.5 billion and are expected to reach $32 billion by 2022) it seems probable that we have passed the point of no return on the road to federal legalisation. So why hasn't the federal government been able to come together to enact cannabis legalisation across the country?

Basically, it is all a question of politics. In the US electorate, most elected Democrats and a handful of Republicans are overwhelmingly in favour of legalising cannabis. But an evenly divided Senate continues to stand in the way of legislative efforts.

In recent years, a number of federal bills to declassify and decriminalise cannabis have been proposed, then passed by the House of Representatives only to hit a Republican wall of obstruction in the Senate. To wit:

- The MORE Act (the Marihuana Opportunities Elimination and Reinvestment (MORE) Act), originally proposed in September 2019 by Representative Jerrold Nadler (Democrats), was the first cannabis bill to succeed at the federal level in Congress. It sought not only to legalise and declassify cannabis but also to legislate reparations for the harm caused by the War on Drugs. It passed the House of Representatives in December 2020 by a margin of 228-164 votes... before dying quietly in the Senate.

- The Safe and Fair Banking Act (SAFE Act), which has passed the House six times since it was first introduced in 2013. If signed into law, the SAFE Banking Act would prohibit federal regulators from imposing penalties on banks that serve licensed marijuana businesses; those businesses would be able to access financial services such as checking accounts and accept credit card payments. The SAFE Banking Act has also not yet come to a vote in the Senate.

- The States Reform Act is another bill that is also now circulating: it was introduced by Republican lawmakers last year. Sponsored by Representative Nancy Mace, the legislation was framed as an alternative to Democratic-led reform proposals and would end federal prohibition. It relinquishes much of the control to the states, proposes a 3% excise tax, regulates cannabis "like alcohol" and offers protections for veterans and cannabis business owners. In this case, it has not even been voted on by Congress yet.

- Finally, legalisation advocates are hopeful that another bill, the Cannabis Administration and Opportunities Act (CAOA), which was scheduled to be introduced on April 1, will give federal lawmakers the opportunity to debate cannabis policy in the Senate. Under the bill, federal tax revenues would support restorative justice (an alternative model of justice aimed at repairing the harm done to the victim) and public health and safety research, with a portion of the funds earmarked for reinvestment in the communities most affected by the War on Drugs. However, 1 April arrived and there was no sign of the announced bill.

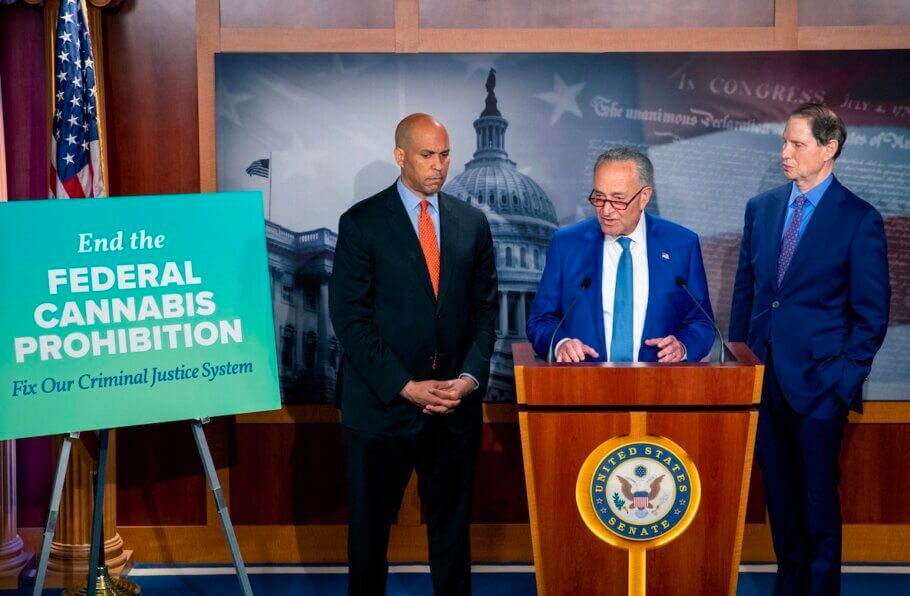

In fact, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (Democrats) made a "promise" to cannabis activists on 20 April (2022) that he will introduce the CAOA bill before the August recess in Congress, tacitly acknowledging in his statement that the previously established deadlines for the long-awaited legislation have not been met.

There may be a point at which political triangulation and partisan manoeuvring will damage federal legalisation attempts, as the various bills that are proposed receive varying levels of support and seek credit to burnish their electoral chances or be supported by members of their own party. Especially now, with a Republican proposal on the table, which will probably make it even less likely that CAOA or the MORE Act will appeal to Republicans as they will want to support the version created by their own party rather than the Democrats. The never-ending political story.

However, as the industry continues to grow, pressure will surely mount on lawmakers to end federal prohibition, one way or another. With more than two-thirds of Americans supporting legalisation and bipartisan support for a federal cannabis policy, it seems likely to happen at some point; until then, and given the circumstances, the individual states' solution may be the best anyone could hope for.