What is Psilocybin and what are its effects?

List of contents

What is psilocybin?

- Name: Psilocybin, 4-PO-DMT

- F0rmula: C12H17N2O4P

- IUPAC name: [3-(2-dimethylaminoethyl)-1H-indol-4-il] dihydrogen phosphate

- Molecular weight: 284,25 g/mol

- Melting point: 220-228ºC

Psilocybin and psilocin (an alkaloid derived from the former) are psychoactive compounds found in numerous species of fungi (estimated at 200 species), including the popular Psilocybe Cubensis. In some areas of the planet, the use of this type of mushroom dates back millennia, either in a recreational or a spiritual form, especially in ritualistic and shamanic contexts. In addition, as we will see later, these entheogens - like many others - can also be used for medicinal purposes, and can be effective to treat diseases such as anxiety or depression.

At the end of the decade of the 50s, using Mexican Psilocybes, the reputed Swiss scientist Albert Hoffman not only managed to isolate psilocybin and psilocin while working at Sandoz laboratories, but also created a way to produce it synthetically. Normally, psilocybin fungi are those that contain this alkaloid compound.

Magic mushrooms & psilocybin

In fact, a large number of mushrooms - often referred to as magic or hallucinogenic - share as a common feature the presence of psilocybin in varying concentrations. There are about 200 basidiomycete fungi that contain it, and can be found naturally in areas of America, Europe and Asia. Naturally, these mushrooms have been used for centuries as a way to "expand the spirit" in the field of shamanism, psychonautics or psychedelic therapy, and in recent years they have become available to grow at home easily thanks to the mushroom cultivation kits available on the market.

The psilocybin and psilocin content of mushrooms will vary depending on the species, although on average they usually make up between 0.1 and 1% of the weight of dry mushrooms. Normally, psilocybin is consumed orally by ingesting mushrooms, either fresh or dried; if improperly stored when dry, psilocybin degrades rapidly, and will barely remain after a few weeks. If, on the other hand, the dried mushrooms are stored correctly, they can remain stable for months.

As we will see below, its effects have led to it being a substance with a wide tradition of use in spiritual and religious contexts, consumed as part of rituals in order to reach a state of consciousness that allows us to journey on the spiritual plane. The Aztec culture, for example, boasts a great tradition in the use of these mushrooms for ritual purposes, which it calls teonanácatl.

Of course, these effects are also widely enjoyed in a recreational context, especially popular during the hippie movement of the 1960s. However, there are a wide range of possible therapeutic or medicinal uses that can be given to these compounds, which means that nowadays they are firmly in the sights of the scientific community.

Effects of psilocybin

Psilocybin is a prodrug, which means that once ingested it is transformed into psilocin within the organism. It is absorbed through the mouth and stomach, and its effects are usually felt between 10 and 40 minutes after ingestion, with a variable duration (2-5 hours or more) that depends on factors such as dose, the species of mushroom or one's own tolerance. For this reason it is always advisable to consume a very small amount the first time to assess the effect achieved and determine whether a higher dose should be used next time. Once absorbed, it is metabolised mainly in the liver where it is converted into psilocin, which in turn is degraded by an enzyme and converted into metabolites that are added to the blood plasma. Its hallucinogenic effects are related to the agonist effect of psilocin on one neurotransmitter in particular: serotonin.

What is Psilocybin and what are its effects?

After decades of neglect, psilocybin is nowadays the subject of dozens of studies and clinical trials all over the world, showing especially promising results in the treatment of conditions like depression or anxiety. In addition to its well-known properties in recreational or spiritual contexts, the news regarding its possible medicinal properties further adds to the interest to this compound.

Normally, tolerance to psilocybin develops and diminishes rapidly; only needing a few consecutive days of consuming mushrooms to build up this tolerance, while after a few days of abstinence it will dissipate, once again giving the same effect as before developing tolerance. It is important to mention that several studies have concluded that this substance does not provoke any type of physical dependence, which is always good news for both the recreational/spiritual consumer as well the therapeutic user.

As with other so-called hallucinogenic substances like mescaline or LSD, the effect can vary greatly depending on factors such as the environment or context, the company around us, and our own state of mind. This is something that the first psychologists studying this type of compounds (including the famously controversial Timothy Leary) focused much of their research on, because they very quickly realised the enormous importance of what they called set and setting when modulating the effect of these substances. After their studies, Leary and his colleagues at Harvard concluded that psilocybin increases an individual's suggestibility, increasing their receptivity to stimuli, something that Berge (1999) corroborated. In this way, factors such as the dose or the type of fungus will be as important as the set and setting, that is, both the environment and context in which the mushrooms are taken, as well as the individual's personal mood or state of mind.

Effects such as an "amplified" perception of colours or geometric shapes are frequent in low doses, giving more of a distortion of reality rather than a hallucination itself. You can experience a feeling of euphoria, but also depression or lethargy. Often, especially in the recreational field, a spiritual connection is felt among the people with those sharing the journey, creating a kind of synergy among the participants of the session. When you close your eyes, you can often see a carousel of shapes and colours, and you can experience the sensation of "seeing music and sounds", which is known as synesthesia.

With higher doses the effect is longer lasting, and the distortions can give way to hallucinations, which can be visual, auditory, tactile... It is not uncommon for the experience to go from a more social level (as in the case of low doses) to a more introspective phase, more entheogenic and meditative, with even mystical overtones. There may also be a modulating effect on the perception of time, in which the present may be perceived as eternal, or give the impression of having entered a temporal loop. Of course, and depending on factors such as those we have already seen, there is always the possibility be a "bad trip", in which the person suffers from anxiety, depression, dysphoria or even panic. For this reason, any good psychonaut will know the best moment for this kind of experience, and also know when it's best to leave it for another time if they don't feel prepared, or can see that the environment won't be conducive to having the desired experience.

Psilocybin to treat addictions, depression or anxiety

The number of studies on the use of psilocybin for the treatment of various diseases or disorders is steadily increasing. Although the first steps into investigation were taken in the 1960s, this was stopped due to the strict laws controlling this type of substances, which grew much harsher during the following decade. It was not until the twentieth century was almost over that this compound once again found itself the focus of attention from doctors and researchers.

Although psilocybin has been used medicinally in certain cultures for centuries, in most countries it has barely been studied at all, due to its legal status. However, modern medical research is increasingly aware of the benefits that its use can offer in the treatment of some condition, especially when using micro-doses. Let's have a look at some examples.

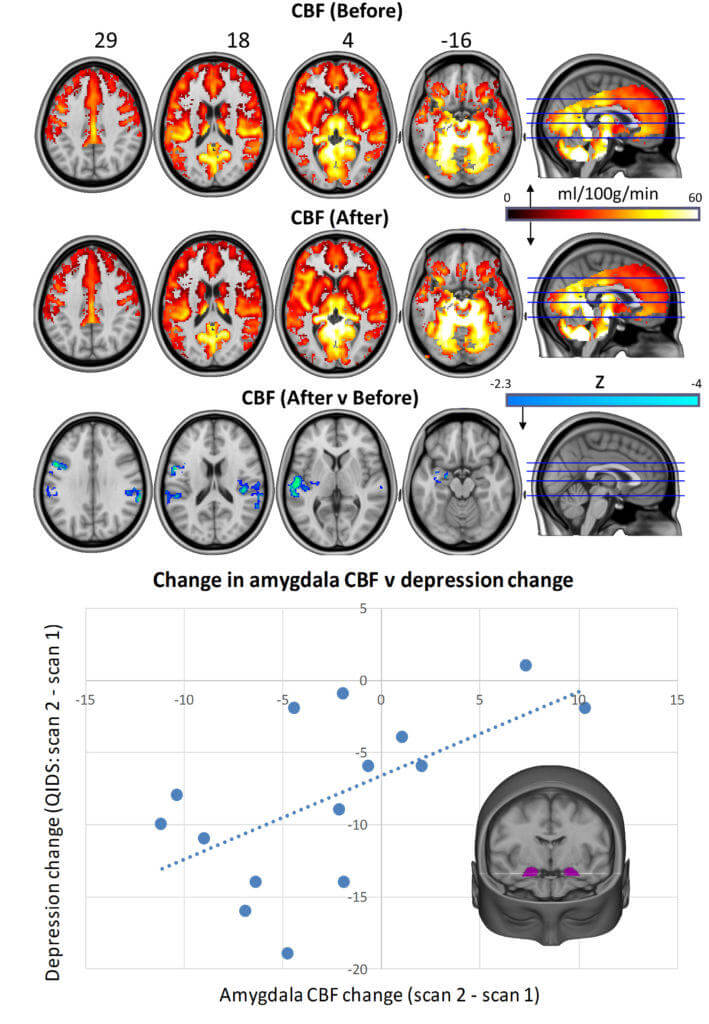

A study by Imperial College London published in the journal Scientific Reports in 2017 concluded that psilocybin had been useful for the treatment of depression in patients for whom conventional therapies had failed. After checking the brain images before and after, they observed a series of changes in the activity of brain areas that precisely control the blood flow in the amygdala, a region involved in the control of anxiety or stress. According to Robin Carhart-Harris, co-author of this study, for the first time there was an almost immediate improvement in the symptoms related to depressive states. Using computer models, psilocybin seems to "reset" the brain in cases of depression, something never before seen.

Similar results were obtained by Roland Griffiths and his team in a clinical investigation carried out at Johns Hopkins University in New York, where they discovered that a single dose of psilocybin had ostensibly decreased symptoms of depression and anxiety in a group of cancer patients. However, medical research goes further than depression and anxiety, other studies have shown promising results when using psilocybin to treat drug addictions, obsessive-compulsive disorders, migraines and headaches (it appears to be especially useful for one of the most devastating types of headache, cluster headaches).

There's no doubt in our minds that we will definitely be hearing more about psilocybin in a medical context over the next few years, as the results obtained so far have surprised even the most optimistic of researchers.

We'll keep you informed!

Bibliography:

- Clinical potential of psilocybin as a treatment for mental health conditions, J. Daniel, M. Haberman

- Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD, Sewell RA, Halpern JH, Pope HG Jr.

- Psilocybin und Psilocin, zwei psychotrope Wirkstoffe aus mexikanischen Rauschpilzen, A. Hofmann R. Heim A. Brack H. Kobel A. Frey H. Ott Th. Petrzilka F. Troxler

- LSD and Psilocybin for Cluster Headaches: Preventing Pain, Saving Lives, R. Wold

- Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial, Roland R Griffiths, Matthew W Johnson, Michael A Carducci, Annie Umbricht, William A Richards, Brian D Richards, Mary P Cosimano and Margaret A Klinedinst

- Psilocybin for depression and anxiety associated with life-threatening illnesses, J. McCorvy, R. Olsen, B. Roth

- Pilot Study of Psilocybin Treatment for Anxiety in Patients With Advanced-Stage Cancer, C. Grob, A. L. Danforth, G. S. Chopra, G. R. Greer

- Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI-measured brain mechanisms, Robin L Carhart-Harris, Leor Roseman, Mark Bolstridge, Lysia Demetriou, J Nienke Pannekoek, Matthew B Wall, Mark Tanner, Mendel Kaelen, John McGonigle, Kevin Murphy, Robert Leech, H Valerie Curran, David J Nutt

- Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation, M. W. Johnson, A. Garcia-Romeu, R. R. Griffiths

- Effects of psilocybin in obsessive-compulsive disorder: An update, C. Wiegand

- Psilocybin, L. Jerome

- Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of Psilocybin in 9 Patients With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, F. Moreno, C. B. Wiegand, E. K. Taitano, P. Delgado

- Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: A proof-of-concept study, Michael P Bogenschutz, Alyssa A Forcehimes, Jessica A Pommy, Claire E Wilcox, PCR Barbosa, Rick J Strassman

- Classic hallucinogens in the treatment of addictions, Michael P. Bogenschutz, Matthew W. Johnson