The Vavilov Institute, the first seed bank in history

List of contents

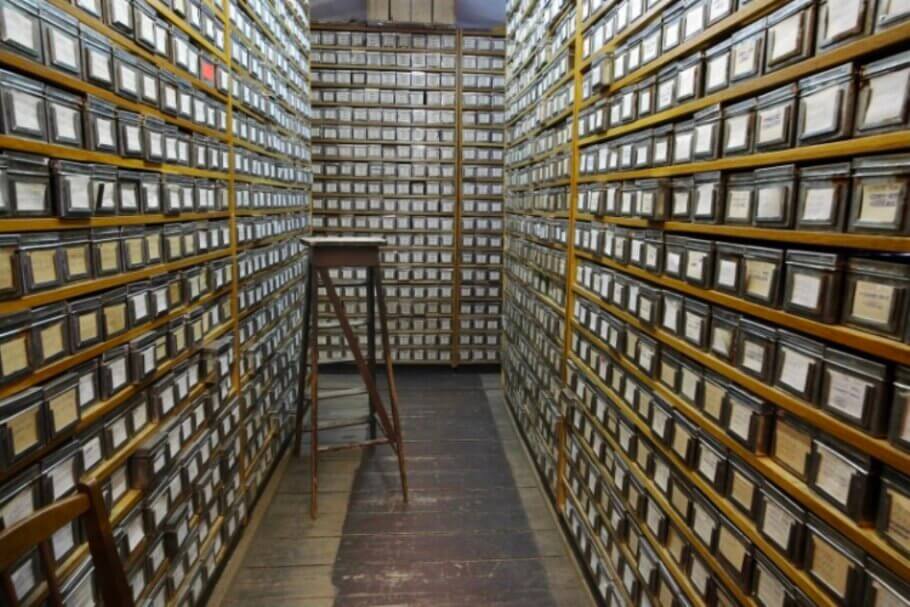

In the heart of the city of St. Petersburg, just behind Saint Isaac's Cathedral, there is a building whose tsarist-era ministerial façade belies the importance of the collection housed behind its walls. Within, stacked under vaulted ceilings and in long hallways, wooden cabinets hold the seeds of hundreds of thousands of plant varieties, many of which have disappeared from their original habitat or growing areas. This is the Vavílov Institute, an institution already hailed as "the guardian of lost plants", a nickname that perfectly illustrates the role it plays as a defence against the new threats to global biodiversity posed by climate change, industrial agriculture, and globalisation.

More formally known as the Vavílov Institute of Plant Industry (VIR), this institution was founded in 1924 by botanist and geneticist Nikolai Vavílov, one of the first scientists to recognise the importance of conserving plant genetic resources. The institute is the oldest seed bank in the world and houses a priceless collection of more than 400,000 samples of different plant species. It is arguably the largest (and oldest) collection of plant genetics in existence, primarily in the form of meticulously catalogued seeds from all parts of our planet.

The Industrial Crops Department of the Vavílov Institute also maintains the largest collection of cannabis germplasm (genetic diversity) in the world; and consists of 397 accessions of cannabis seeds (an accession is a batch of seeds of a species that has been collected in a certain place and at a certain time) from three basic ecogeographic groups: North, Central, and South, collected in dozens of nations over more than a century. The collection represents wild and traditional cultivated cannabis varieties, as well as products from plant improvement programs, many of which are not to be found in any other gene bank.

Under normal storage conditions, cannabis seeds can be kept for about 5 years before losing viability. Therefore, maintaining a cannabis collection like this involves reproducing the genetics at least once every 5 years.

Since the breakup of the Soviet Union, funding for the Vavílov Institute has decreased dramatically, threatening the maintenance of its collections. And if the VIR's cannabis genetics are not reproduced, they are destined to become extinct before their true value is recognised and used. In light of the renewed interest in cannabis worldwide, it would be very unwise to let this gene pool die, especially taking into account that this is not the first time that the Institute has gone through difficult times, weathering the ups and downs of history in a truly heroic way.

The botanists who chose to starve to save their collection

To get an idea of its epic past, just learn how its collection miraculously survived WWII, when starving scientists guarded vast reserves of seeds to prevent them from being eaten when food was scarce. During the siege of Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), which lasted 872 days, the workers charged with taking care of the Vavílov Institute's collection faced an unthinkable decision.

As the city prepared for the German attack, the Soviets hurried to remove thousands of works of art from the Hermitage Museum to safeguard them; but officials refused to protect another, equally priceless collection which was, at the time, arguably the largest seed collection in the world. With the director of the Institute, Nikolai Vavílov, imprisoned (later we'll recount his epic story), the scientists who worked there took on its defence as their responsibility. They found refuge with the huge cache of seeds, boarded up the bombed-out windows of the building and turned their workplace into their shelter.

The winter of 1941-1942 was especially cold and cruel in Leningrad, with constant bombardment and all food supplies to the city cut off. The people were forced to eat anything: dogs, cats, rats, dirt, and even human corpses because stricken by hunger, thousands recurred to cannibalism, in the most terrifying scenes from this futile battle that cost the lives of a million of the city's inhabitants.

Workers at the Vavílov Institute agreed to rotate guard shifts, protecting the seeds against threats that ranged from intruders to rats and even to their own hunger. Paradoxically, the rats came close to achieving what the Nazis couldn't, but the guardians of these genetic treasures were able to react in time, devising different stratagems to keep the seeds safe from rodents.

At the end of the infamous and brutal campaign, many of these botanists and staff of the institution (an estimated thirty) had died from starvation while protecting the collection, inside the building while they were literally surrounded by food. The curator of the rice collection died surrounded by sacks of rice. The tuber scientists who oversaw the Soviet Union's vast collection (with 6,000 preserved varieties), succumbed in the cellar while protecting the potatoes to the last.

If they had germinated the seeds and eaten their fruits, all the work of their predecessors would have been lost. Their mission was to catalogue and preserve genetic material for the expansion of knowledge, for all, even in the middle of a world war, with society collapsing all around them.

The seeds that saved the USSR from starvation

Their deaths were a leap of faith that things would improve, because these botanists and workers at the Vavílov Institute were convinced that, beyond their value to science, the seeds were going to be essential to any recovery after the conflict. They were not wrong: some estimates indicate that 80% of postwar Soviet crops came from that seed store. The enormous quantity of horticultural seeds and their meticulous classification made it possible to find those that were best adapted to the war-torn terrain and climate of each region. Without a doubt, they were instrumental in preventing famine in the Soviet Union.

The collection of seeds compiled by the Vavílov Institute is reflected in the almost 1,400 seedbanks in existence today. One of the most important is the Millennium Seed Bank, managed by Kew Botanical Gardens (United Kingdom), which houses some 34,000 plant species, representing 13% of the wild species on our planet. Other seed banks have followed, for example, the impregnable Svalbard Global Seed Vault, also known as the "Doomsday Vault" which was opened in Norway in 2008 as a "backup" of the most important treasures of the world's seed banks, where they store frozen samples of their seed collections that can be replicated in the case of loss caused by armed conflicts, terrorist acts or natural disasters.

But none carry as much emotional weight or have such a moving story as the one stored in filing cabinets in the heart of St. Petersburg. Today, the Vavílov Institute continues to function thanks to the sacrifices of a handful of dedicated and principled human beings. All of the same seeds that Nikolai Vavílov and his workers lost their lives conserving are still in the collection, when not being shared with other research institutes around the world, with a growing collection of new specimens contributed by these modern banks in return.

The tragic and ironic fate of Nikolai Vavílov

The institution holds the fruit of twenty years of research carried out by one of the most unsung heroes of 20th-century science: the Russian botanist and geneticist Nikolai Vavílov, who dedicated his life to trying to eradicate hunger in the world. But during the siege of Leningrad, the seed bank was already without its director.

Through thick and thin, the scientists of the Vavílov Institute have maintained the collection to this day, sacrificing their lives for it

Without a doubt, the beginning of this story can be found in the project started 20 years earlier by Vavílov, considered the "father of modern seed banks" and who journeyed to many countries (North America, Afghanistan, China, Japan, Korea, Latin America...), building the largest seed collection of the time. His idea was that cultivated plants have "centres of origin", that is, places where their selection, domestication, and improvement began; and in which one can find wild varieties of each current species.

This biologist also made one of the first important advances in plant genetics by presenting the "Law of homologous series in hereditary variation," which, among other things, predicted the probability of discovering new varieties of plants.

Although at first, he was a very prestigious scientist who, during the first years of his career, had enjoyed the support of the Bolshevik government (even receiving the Lenin Prize, something like a Soviet Nobel Prize), after Lenin's death, Vavílov's situation became more complicated and he fell out of favour for defending genetics, which for the Soviets was "bourgeois pseudoscience."

Stalin believed in a now-discredited scientific hypothesis: the inheritance of acquired characteristics. The socialist "man" would beget socialist offspring. Trofim Lysenko, his trusted science advisor, backed him up. As this Ukrainian agronomist claimed then, genetics was a science invented by capitalism to give a biological justification to class differences. Lysenko argued that evolution was guided by the "inheritance of acquired traits", a line of thought that derived from Lamarckism and was opposed to natural selection. So Nikolai Vavílov, the true scientist, was considered an enemy of the state for not following this line of thought and was arrested and imprisoned in 1940, a year before the siege of Leningrad began.

An undying legacy for generations to come

But before being condemned to oblivion, Nikolai Vavílov helped transform the study of botany and was one of the first scientists to listen to farmers, including traditional farmers and peasants, who felt that seed diversity was important in their fields. Vavílov amassed a collection of some 220,000 different varieties of seeds, which led to the creation of eight crop breeding centres of origin, scientific cultivation stations scattered throughout the Soviet Union that allowed him to experiment with different species in different climatic zones. In this way, he wanted to discover which were the ideal crops for each one. His commitment and dedication to seeds is unmatched and shows his concern for the future of agriculture.

During his life, he realised the importance of saving seeds, but due to Stalin's collectivisation of private farms, turning them into assembly lines, farmers could no longer own their land or control their crops. Stalin used Vavílov as a scapegoat, blaming him for the hunger and failure of his agricultural collectives, locking him up like a dog in a remote gulag. After more than 18 months of surviving on frozen cabbage and mouldy flour, the botanist who strived for more than 50 years to end world famine, died of hunger.

Today Nikolai Vavílov, although little known beyond the history books, occupies a prominent place in the ranks of illustrious men of science. His memory was restored almost three decades after his death when, in 1968, the institute he founded in Saint Petersburg was renamed as the Vavilov Institute for Plant Industry. Happily, his enormous effort and that of his collaborators certainly paid off in the end.

References:

- Large-scale whole-genome resequencing unravels the domestication history of Cannabis sativa. Nicolas Salamin, Luca Fumagalli, Ying Li, Kate Ridout. 2021 Jul 16

- Vavilov and his Institute. A history of the world collection of plant genetic resources in Russia. Por Igor G. Loskutov (Frankel Fellow-1993)