This is how psilocybin affects your brain

List of contents

- Psilocybin, the main psychoactive component of magic mushrooms

- Psilocybin and the brain

- Receptors involved: the role of serotonin

- Interaction with dopamine and other neurotransmitter pathways

- Relationship with the amygdala: fear, anxiety, and emotional response

- Brain network desynchronization: the “default mode” and beyond

- Brain cell growth: neurogenesis and plasticity

- Long-term effects: lasting changes?

- How does psilocybin affect your mood?

- Psilocybin as a substitute for antidepressants?

- Combined use of psilocybin and other drugs

- Psilocybin for the treatment of addictions

For centuries, different cultures have turned to so-called "magic or hallucinogenic mushrooms" not only as a vehicle for spiritual connection, but also as a healing tool. What was once considered an ancestral ritual is now capturing the attention of modern neuroscience. The reason? A compound called psilocybin, capable of altering perception, modulating brain activity, and, with increasing scientific support, offering relief from disorders such as depression and anxiety.

As research on psychedelics gains a foothold in clinical settings, it's crucial to understand how this substance acts in the brain. What mechanisms does it trigger? Which brain regions does it affect? Can its effects really be compared to those of conventional antidepressants? In this article, we aim to shed light on these and other questions by analyzing the most recent studies. Will you join us?

Psilocybin, the main psychoactive component of magic mushrooms

Psilocybin is a tryptamine alkaloid found in more than 180 species of mushrooms of the genus Psilocybe, among others. After ingestion, the body rapidly converts it into psilocin, the active metabolite responsible for its psychoactive effects. This molecule, structurally similar to serotonin, can cross the blood-brain barrier and act directly on neuronal receptors.

Although psilocybin's popularity rose in Western culture during the 1960s counterculture era, thanks to figures like Timothy Leary and pioneering research at Harvard, its use dates back to pre-Columbian times. Mesoamerican civilizations, such as the Aztecs, already used these mushrooms for religious and medicinal purposes, under the name teonanácatl ("flesh of the gods").

Today, far from the stigma, psilocybin is being re-evaluated by the scientific community, with studies pointing to its therapeutic potential in very specific and controlled contexts. From clinical trials on drug-resistant depression to research on its ability to induce neuroplasticity, this molecule is now enjoying a second life, albeit with a white coat, microscope, and science as its backdrop.

Psilocybin and the brain

Receptors involved: the role of serotonin

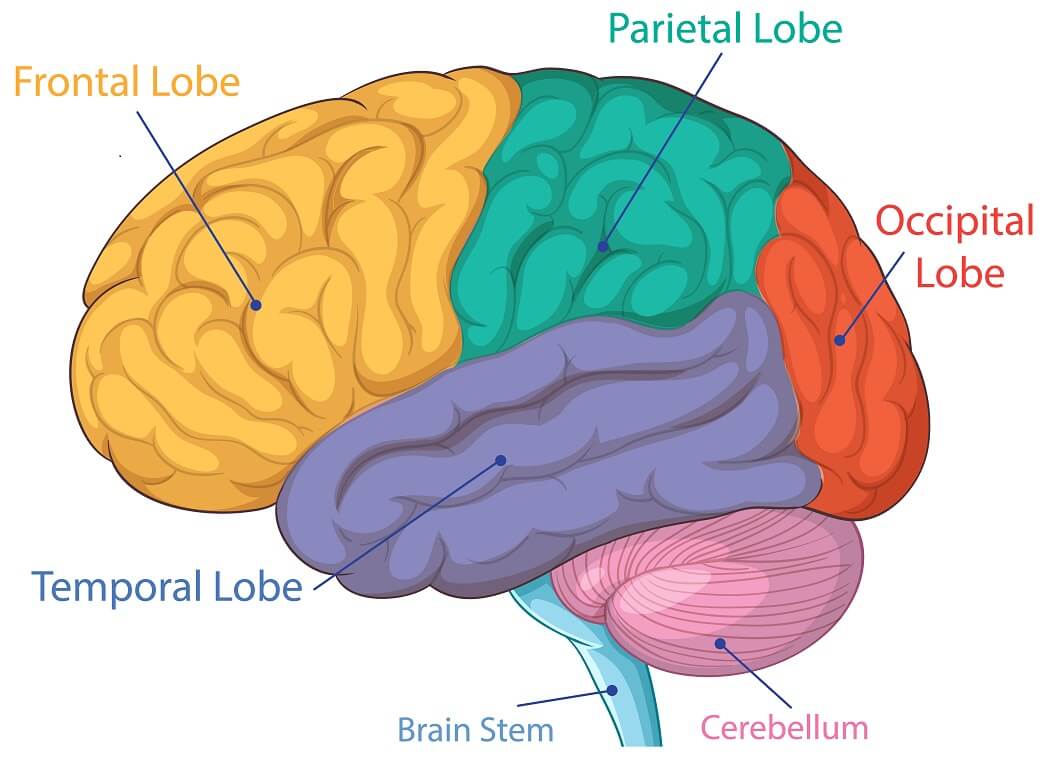

The primary target of psilocin (the active metabolite of psilocybin) in the brain is the 5-HT2A receptor, a subclass of serotonin receptors. This receptor is widely distributed in the prefrontal cortex, a region associated with higher cognitive functions such as abstract thinking, decision-making, and emotional regulation.

When activated, these receptors trigger a cascade of signals that alter the brain's normal dynamics. Far from being limited to a simple "increase" in serotonin, what occurs is a profound reconfiguration of brain activity, involving multiple neural networks.

Interaction with dopamine and other neurotransmitter pathways

Although psilocin's most prominent effect is through the serotonergic system, there are indirect interactions with other neurotransmitters, such as dopamine. Some studies suggest that 5-HT2A activation can modulate dopamine release in areas such as the striatum or the mesolimbic circuit, which are involved in reward and motivation.

This interaction could help explain the subjective sense of “insight” or inner discovery that many users experience, as well as certain changes in emotional processing.

Relationship with the amygdala: fear, anxiety, and emotional response

The brain's amygdala, the nerve center for processing fear and anxiety, shows reduced activity under the influence of psilocybin. This has been demonstrated in functional neuroimaging studies, which show a decreased reactivity of this structure to negative or threatening stimuli.

This phenomenon could be behind the anxiolytic effects observed in patients with disorders such as depression or generalized anxiety disorder. Rather than "blocking" emotions, psilocybin appears to facilitate a more flexible approach to emotional experience.

Brain network desynchronization: the “default mode” and beyond

One of the most consistent findings in recent psychedelic research is the temporary dissolution of the Default Mode Network (DMN), a brain network that activates when we are mentally at rest, ruminating, or focusing on ourselves. Under psilocybin, this network loses its usual coherence, which is associated with the experience of “ego dissolution,” so commonly reported by a large number of users.

At the same time, increased connectivity is observed between brain regions that don't normally communicate with each other, resulting in a freer, less hierarchical pattern of neuronal activity. In other words, the brain stops following its usual highways and explores secondary paths, with results as varied as they are revealing.

Brain cell growth: neurogenesis and plasticity

One of the most promising discoveries concerns neurogenesis and neuroplasticity. Animal models and human visualization tools have shown that psilocybin can stimulate the growth of new synaptic connections and promote neuronal branching, especially in the prefrontal cortex.

This effect could underlie its therapeutic potential, as depression and other mental disorders are often associated with reduced brain plasticity. Thus, psilocybin not only momentarily alters perception but could also open a "window of opportunity" for long-term psychological restructuring.

Long-term effects: lasting changes?

Although the subjective duration of a psilocybin trip is typically limited to a few hours, its long-term effects can persist for weeks or even months. Longitudinal studies have shown sustained improvements in mood , a reduction in depressive symptoms, and greater psychological openness in participants.

These effects appear to be mediated, at least in part, by functional changes in brain connectivity and a new way of processing thoughts and emotions, even after the substance has been eliminated from the body.

How does psilocybin affect your mood?

One of psilocybin's most notable effects is its ability to modulate an individual's emotional state, even long after it has left the body. Far from being a simple "high," its impact on mood responds to a combination of neurobiological and psychological factors acting at different levels.

During the acute experience, many people report a significant increase in well-being, a sense of deep connection with oneself, others, or one's environment. Clinically, this experience can translate into a reduction in negative affect , increased tolerance for unpleasant emotions , and a more open attitude toward psychological distress.

One of the key mechanisms here is the alteration of emotional processing. Psilocybin appears to facilitate a kind of affective "reset," in which repressed or bottled-up emotions can surface, be processed, and released. In clinical studies, participants have been observed not only to experience an improvement in their overall mood but also to re-evaluate painful memories with less emotional baggage, which can have a lasting therapeutic effect.

For people with depression, this ability to reconnect with the emotion without getting caught up in it is especially valuable. As some patients in clinical trials have described, "It's not that the sadness disappears, it's that it no longer has the same power over me."

Furthermore, increased cognitive flexibility has been identified after psilocybin use, a change that translates into less mental rigidity and greater openness to new perspectives. This phenomenon, difficult to quantify but consistent across multiple studies, could explain why many people report experiencing "a new way of seeing life" after a single controlled session.

It's important to remember that the effects on mood are neither automatic nor universal. The quality of the psychedelic experience depends on multiple factors, from the dose to the setting and therapeutic support (set & setting). In clinical contexts, these elements are carefully considered precisely to enhance the benefits and minimize the risks.

Introduction to microdosing psilocybin

As we mentioned in our article on psilocybin and its effects, the use of this substance in various therapies is becoming more common, especially in the form of microdoses. Today we offer you a brief but succinct guide on psilocybin microdosing: what it is, how it works, and what are the recommended doses, are only some of the topics we will be discussing below.

Psilocybin as a substitute for antidepressants?

The possibility that a single or a few doses of psilocybin could have effects comparable to—or even superior to—weeks of treatment with traditional antidepressants has generated enormous interest in the medical community. And with good reason. In a context where major depression remains one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, the search for more effective therapies with fewer side effects is a priority.

Studies such as those conducted by Imperial College London and the NYU Langone team have shown that psilocybin, administered in controlled settings and with therapeutic support, can significantly reduce depressive symptoms in patients with treatment-resistant depression. In some cases, improvement persists for weeks or months after a single session.

One of the key differences with conventional antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), is the mode of action. While SSRIs act chronically, artificially elevating serotonin levels in the synapse, psilocybin appears to reactivate deep emotional mechanisms and stimulate neuroplasticity, paving the way for psychological restructuring that doesn't depend on continuous use.

Furthermore, patients often describe a qualitatively different improvement. It's not simply that they "feel less sad," but rather that they regain interest, emotional connection, and the ability to experience pleasure —aspects that SSRIs often fail to fully restore.

On the other hand, we must be cautious: this is not a magic bullet, nor is it intended for home or recreational use. Psilocybin alone does not replace therapeutic support, and its transformative potential requires a structured environment, with prior preparation and follow-up. It is a powerful tool, but not a stand-alone tool.

To this day, clinical trials continue to accumulate evidence, and some regulatory agencies—such as the FDA in the US and the Paul Ehrlich Institute in Germany—have already granted these treatments "breakthrough therapy" status. Are we witnessing the future of psychiatry? It's too early to say, but the cards on the table invite us to look beyond the traditional prescription.

Combined use of psilocybin and other drugs

Although psilocybin is relatively safe in controlled clinical settings, combining it with other substances can be problematic. Combining it with antidepressants, especially SSRIs, can reduce its effect or, in rare cases, cause serotonin syndrome. Therefore, in clinical trials, conventional medications are often discontinued before administering them.

Recreational use with other drugs such as cannabis, MDMA, or alcohol increases the risk of adverse reactions, such as intense anxiety, confusion, or unwanted physical effects; in other words, what is considered a bad mushroom trip. Furthermore, people with a history of psychotic disorders should avoid use, as it can trigger serious episodes.

In short, Psilocybin is not a substance to be mixed without medical knowledge or supervision. Interactions can be unpredictable and, in some cases, dangerous.

Without a doubt, a bad mushroom trip is a truly intense experience for those who experience it. But why do these bad trips occur? What is the cause of these types of effects? Can anything be done to stop or mitigate them? Today we answer all these questions.

Psilocybin for the treatment of addictions

Various clinical studies, such as those at Johns Hopkins, have shown that psilocybin, in combination with therapeutic support, can help patients overcome addictions such as alcohol, tobacco, or opiates. How does it do this? By facilitating deep introspective experiences that allow patients to review their behavior from a different perspective, with less judgment and more clarity.

At the brain level, it acts on reward and habit circuits and promotes neuroplasticity, which facilitates the learning of new behavior patterns. Important: it is not a detoxifier or a magic cure. It only works well in controlled clinical settings and with psychological support.

Bottom line: Psilocybin doesn't magically eliminate addiction, but it can be a powerful tool to help break compulsive cycles when traditional treatments aren't enough.

In just a few decades, psilocybin has gone from being viewed as a remnant of the counterculture to occupying a prominent place in neuroscience and psychiatry laboratories. And it has done so with good reason: accumulating data shows that its ability to modulate brain activity, unlock rigid emotional patterns, and promote neuronal plasticity make it a serious candidate for the treatment of complex disorders such as depression, anxiety, and addiction.

However, it's important not to be carried away by unqualified enthusiasm. Psilocybin is not a panacea, nor is it without risks. Its therapeutic potential is only fully realized when administered with clinical rigor, in prepared settings, and with a deep understanding of the patient's psychological context. It's not so much a pill that magically cures, but rather a new door that opens... as long as you know how and when to cross it.

With each new study, we learn more about the brain, but also about ourselves. And perhaps that's the most interesting thing: that, at its core, what psilocybin seems to offer us isn't answers, but the possibility of asking the right questions.

Let the investigation continue!

References:

- Psilocybin desynchronizes the human brain, Nature Magazine

- How Psychedelics Affect the Brain, American Brain Foundation

- Psychedelic Drug Therapy May Address Mental Health Concerns in People with Cancer & Addiction, NYU Langone

- How psychedelic drugs alter the brain, NIH (National Institutes of Health)

- Psilocybin modulates functional connectivity of the amygdala during emotional face discrimination, O. Grimm, R. Kraehenmann, K.H. Preller, E. Seifritz, F.X. Vollenweider

- How psilocybin, the psychedelic in mushrooms, may rewire the brain to ease depression, anxiety and more, Sandee LaMotte, CNN

- New tool tracks how psychedelics affect neurons in the brain, Greg Watry, UC Davis